Overview

Entering a UCD Innovation Academy module and you, like many of our students, may think that you have taken a wrong turn. This is not what you remember formal education to look or feel like. Why do you need to bring a personal object from home? What do ducks have to do with creativity? And why will you never look at a phonebox the same way?

What you have stumbled upon is a unique approach to experiential learning within Higher Education in Ireland. Established in 2010, UCD Innovation Academy has developed its craft for 14 years to deliver transformational learning experiences for the benefit of society, the economy and the planet. In this article I will share some of what we have learned about experiential learning. If you are an educator, a facilitator or involved in any aspect of helping people learn then we hope you find it useful.

Step 1

1. Be confident that experiential learning is evidence-based and will have a positive impact on student engagement and learning.

We didn’t make it up. It would be great if we did but by employing experiential learning as our main pedagogical approach in the UCD Innovation Academy, we are simply bringing to life existing evidence and pedagogical theory.

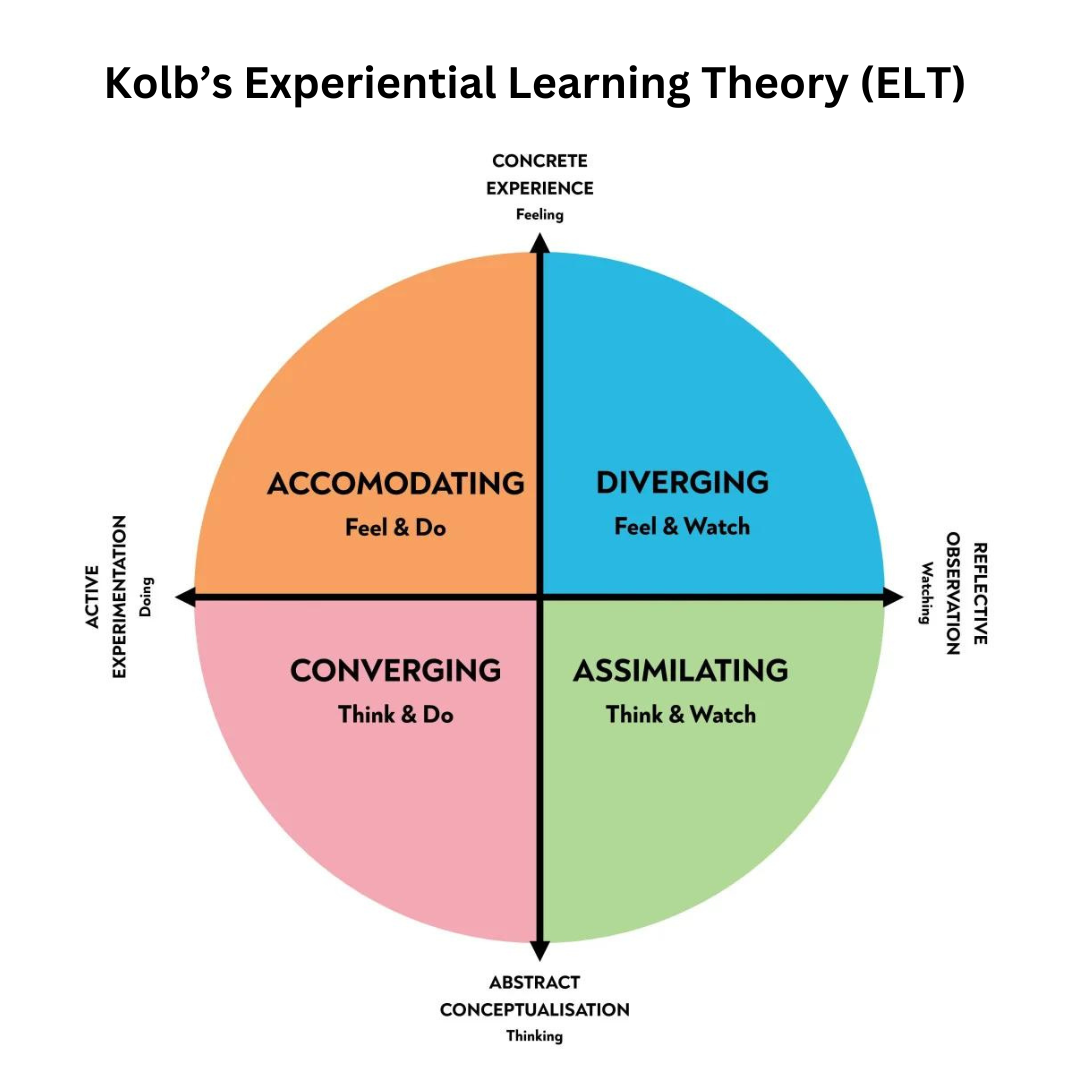

Many educators will be familiar with Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory (ELT) which synthesises the work of other prominent 20th century scholars, including Lewin, Dewey and Piaget. The central tenet of their work is that learning occurs when we interact with the environment around us. Experiencing something is the catalyst, but learning will only occur if we engage with the experience in a meaningful way. In Kolb’s experiential learning cycle this involves reflecting on the experience, thinking about it to draw conclusions, and finally taking action to put it into practice.

The evidence shows that this approach now only improves student engagement, but also mirrors our natural instincts for learning. In contrast to conventional, didactic classrooms, in experiential learning the learner takes a more active role in leading their own learning.

Step 2

2. Create an ‘Experience’ for Your Students

You might be wondering what constitutes an experience?

In essence, an experience can be defined as an event or an occurrence that leaves an impression on someone. It could be something that engages the senses, evokes emotion or is novel for the participant. It does not have to be big or showy. A thought-provoking question can produce an experience, just as an immersive role-play activity can.

An experience must have an impact and therefore it cannot be something that you do on auto-pilot. This means that different people will experience activities differently. For example, some people will be completely unphased speaking in front of a group as they do it regularly. For others, public speaking might be totally out of their comfort zone and leave them feeling anxious. This doesn’t mean the confident public speaker will gain nothing from a presenting activity – in fact, they may be struck by a new realisation or awareness of others’ through the experience of listening to their less-confident peers reflect. The ‘experience’ they are learning from is different, but both can have a significant impact on the individual.

Step 3

3. Learn ‘from’ Doing not Learn ‘by’ Doing

In the UCD Innovation Academy we differentiate between learning ‘by’ doing and learning ‘from’ doing. For us, learning-by-doing is a hands-on approach and the process of learning through the activity. For example, learning to ride a bike is often achieved by getting on and having a go. A subtle, yet important, difference in learning-from-doing is that the learning occurs after the doing has taken place.

For us, the activity or hands-on aspect of the experience is simply the stimulus for learning. The real learning takes place in the stages afterwards; reflection, dialogue, meaning-making and applying to different contexts.

One example is our VR for Future Skills module. This fully accredited module for undergraduate students is designed on the principles of learning-from-doing. Note how it follows Kolb’s cycle:

- VR Room: Students complete a room in the VR programme each week at home. (Concrete experience)

- Individual and Peer Reflection: Students meet with their small action learning set to answer prompt reflection questions relating to the room. (Reflection)

- Facilitated session with the whole class: An Innovation Academy facilitator hosts structured activities to support the class to make sense of the themes, draw conclusions and apply their new thinking to a range of different contexts. (Thinking and Acting)

Of course just completing the VR room would provide an opportunity for learning but it is limited to the individual. The power of providing time and space to learn from the VR experience as part of a group significantly increases the potential of making an impact on the learner, and ultimately creating a lasting change.

Step 4

4. Create Psychological Safety

In an experiential learning classroom, you are constantly asking students to step out of their comfort zone either to try something new or to be vulnerable in reflection. For this to work, you have to create a culture of psychological safety (trust) whereby everyone feels confident that they can engage fully without risk of being ridiculed or excluded from the group.

Creating psychological safety is fundamental to our classes at the UCD Innovation Academy. Every facilitator takes time to carefully plan how to establish it at the beginning of a new module or event, and also how to sustain it throughout the course. We have a range of techniques to draw upon (this might warrant its own How To Guide!) but here are a few suggestions to get you started:

- Don’t assume that psychological safety will naturally emerge. Be intentional about how you will curate it and take time to plan it when designing courses.

- Go beyond token ice-breakers. Of course these informal, getting-to-know-you moments have a place but creating a culture of psychological safety should underpin every activity and aspect of how your students will work together in your class community.

- Be explicit. You might develop a class charter or code of conduct with your students. This should be visible and clearly outline expectations and acceptable behaviours.

- Model it. Students need to trust you as part of building trust in the module and with each other. If you say you will finish at a particular time, make sure you do. Be open yourself about what you’re learning and where you are improving. This will help others feel safe to do the same.

Step 5

5. Reimagine Your Role

In traditional learning environments it is usual to see the teacher, lecturer or trainer delivering content from the front of the room. This ‘sage on the stage’ is often a default for educators. This can be for a range of reasons. Some may associate it with professionalism, their own experience of education or in some cases, it is a way of compensating for imposter syndrome to be the most knowledgeable person in the room.

In an experiential learning environment the educator must shift their perspective to acknowledge the wealth of experience and potential that their students bring. Opening space for students to contribute to, and ultimately co-create, the learning results in a dynamic and vibrant classroom where unexpected things can happen.

To achieve this, it is necessary to reimagine the role of educator. Some of the different hats a facilitator of experiential learning might wear include:

- Learning Designer: You curate the overall learning experience. Choice of activities, discussion prompts, timings, groupings, physical space configuration etc all matter as part of the experience. You don’t ‘wing’ it but you give serious consideration to the arc of a learning journey and the student experience.

- Facilitator: You go beyond ‘teacher’, creating opportunities for meaningful experiences that you support students to make sense of. You facilitate activities, reflection, dialogue, goal-setting etc, helping students to lead their own learning. You set the pace, allowing time for unexpected conversations, but are responsible for steering the group to achieve the agreed learning goals.

3. Relationship Builder: You get to know your students and help them to get to know each other. Intentional community building is part of your planning. The better you know students, the more effectively you can offer opportunities for individuals to share their expertise or experiences, shifting into a peer-learning environment based on mutual respect.

4. Responsive & Adaptive Practice: You are attuned to the ‘weather’ in the room, you make adjustments in the moment responding to the energy of the group – do you need a quick energiser, break or quiet focus time? You carefully listen to both what students say and what they don’t. You use this information to adapt in real-time to meet their needs. For example, reframing something or drawing out someone’s expertise to add to the overall experience.

Step 6

6. Upskill Yourself

Facilitating experiential learning requires you to be flexible and adapt to the students in front of you. Being flexible is easiest when you are confident that you have a range of tools and techniques that can be deployed at the appropriate time and for different purposes. The best thing you can do is to engage in your own professional development and join a community of like-minded peers who will support you to embrace your role.

If you wish to know more about our approach and are interested in joining our next programme aimed at Educators who wish to develop their practice you can read more about the programme here: UCD Professional Certificate/Diploma in Creativity & Innovation for Education.

Further Reading

Further Reading:

- Institute for Experiential Learning: What is Experiential Learning?

- University of Queensland, Australia: Experiential Learning: An Overview

- McKinsey & Company: Psychological Safety and the critical role of leadership development

- Ji Won You (2021) Enhancing creativity in team project-based learning amongst science college students : The moderating role of psychological safety, Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 58:2, 135-145, DOI: 10.1080/14703297.2020.1711796